Subtle as a sledge hammer … you could be reading Britain’s Sun or an ABC news digest but this is Middle East Monitor‘s breaking news for December 19, 2016. And, to be fair, there are subtle cultural variations

FATHERS in Eastern Aleppo are asking religious scholars if it is cool to kill their daughters before they are “captured and raped by Assad, Hezbollah, and Iranian militias”, Middle East Monitors reports.

The publication, sometimes accused of links with the Muslim Brotherhood, selects and republishes material from across the region. The tasty titbit above came from publications in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

It is crude war propaganda that appeals to the cultural and religious views, some would say prejudices, of its readers.

It is different from the war propaganda being hammered out by mainstream western news sources but only very superficially.

This story was repackaged for western audiences where, generally speaking, most readers no longer agree that religious scholars should have the right to decide whether women live or die.

It ran, just like the Middle East Monitor version, as an “our enemy is a beast story”, devoid of facts or any obvious checking. And, as a general editorial rule, the more heinous or extreme the accusation, the more rigorous fact-checking should be.

“Scores of Aleppo women commit suicide to avoid being brutally raped by Assad’s troops,” the headline in Britain’s always dubious Express newspaper announced.

The Mirror and News Corp publications, including the notorious Sun, followed suit. Even Marie Claire gave it a run though not quite as breathlessly.

American newspapers and websites absolutely loved it. The New York Times, Vice, Daily Beast and something called the Christian Post were all over it like a rash.

Note the subtle cultural differences, though. In the enlightened west, brave independent women were given agency over their own deaths. Empowering stuff, no doubt.

But it was essentially the same story, published on the same day with the same lack of ethical standards for the same obvious reasons.

The other big difference between Islamist-oriented publications and their western allies, other than not much, is the international tastes they satisfy.

In the west, courtesy of 99 years of cold war demagoguery, it is Russia and Vladimir Putin, who are the undisputed targets of most associated vitriol.

In the Arabian Gulf, however, Vlad barely gets a mention. Instead, it is region’s non-Arab power, Iran, and its leadership who cop endless sprays of venom.

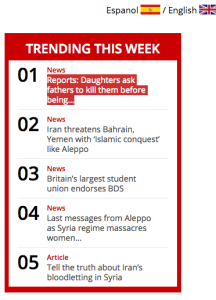

On December 17, 2016, Middle East Monitors top five news stories, in order, were these…

— Daughters ask fathers to kill them before being raped by Assad forces

— Iran threatens Bahrain, Yemen with ‘Islamic conquest’

— Britain’s largest student union endorses BDS

— Last messages from Aleppo as Syria regime massacres women and children

— Tell the truth about Iran’s bloodletting in Syria

Amongst a herd of similar beasts roaming Middle East Monitor’s well stocked opinion pages, lurked some close relations … Time to make Syria ungovernable for the terrorist Assad … As death rains down on Aleppo, why are western countries so reluctant to act? … The ‘let them bleed’ doctrine in Syria … Iran’s attempted genocide of the Sunni Arabs … Violence is everywhere and Iran must take the blame

Phew!

On the same day, the sometimes liberal, British Independent newspaper was quoting former Foreign Secretary and Labour Party luminary, David Miliband as announcing, from a comfortable spot in the UK no doubt, “house-to-house murder” was being carried out in Aleppo.

Miliband was speaking on behalf of a US “aid agency” that has added him to the payroll.

It is no wonder that two of the Independent’s best journalists, and most respected foreign correspondents, Robert Fisk and Patrick Cockburn, were moved to again warn colleagues about their coverage of Syria.

Irish-born Cockburn was the Financial Times’ Middle East and Moscow correspondent before joining the Independent in 1990. He specialises in Iraqi and Syrian issues and was one of the first westerners to forecast the rise of DAESH.

For what it is worth, Beirut-based Arab speaker Fisk has been voted British International Journalist of the Year seven times and has been honoured by Amnesty International for his work. For half a century he has interviewed trouble makers and history makers across the Middle East, including Osama bin Laden and Hafez al-Assad.

Neither Fisk nor Cockburn can be described as even moderately pro-Bashar al-Assad, far from it. But they know the region and its history. More importantly, they know their trade and its ethics.

Both are worried by the endless stream of bullshit being flushed out of Syria.

Cockburn goes further, arguing the media’s willingness to uncritically adopt partisan Syrian activists as preferred news sources is a grevious mistake. It will, he warns, lead to independent journalists being kidnapped and murdered more often.